The Studio Ghibli adaptation of the late Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series is notoriously bad. I’d heard the same reviews from Le Guin and Ghibli fans alike, long before I ever watched the 2006 film, and even long before I read the Earthsea novels themselves. Whitewashed, plodding pace, and a bizarre mash-up of four novels, a graphic novel, and a host of short fiction, the film seemed to garner even more vitriol than the average book-to-film adaptation (which is, let’s be real, a high bar).

When I finally sat down to watch this dark horse of the Ghibli oeuvre, my inclination wasn’t to like or dislike the thing, but to understand why the meeting of these worlds could fail so spectacularly in the eyes of the creators’ fans. After all, so much of what makes Ghibli and Le Guin wonderful is shared, the absolute beauty of their artforms aside. I’ve loved Ghibli since before I could read, and loved Le Guin since the first sentence of The Left Hand of Darkness. So why, within the first five minutes of their meeting, was I filled with more dread than excitement?

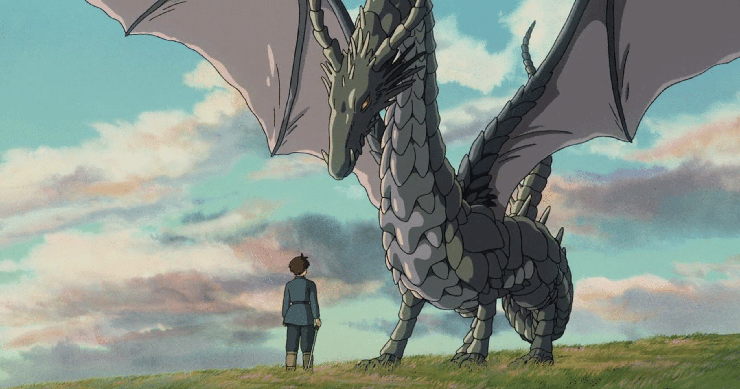

First, a brief overview: Tales of Earthsea was not directed by the much-lauded founder of Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki, but instead by his son and first-time director Gorō Miyazaki. It follows Prince Arren after he mysteriously murders his father and flees his kingdom, happening upon the mage Sparrowhawk only by chance. Sparrowhawk, who is investigating the disappearance of magic in the realm, takes Arren under his wing (literally! His scar is in the shape of a wing on his face, and it’s my favorite part of the movie). Arren rescues a young girl from slavers, who he later discovers is Therru, adopted daughter of Sparrowhawk’s friend Tenar. Therru is suspicious of Arren due to his bloodlust in battle, but comes around to him after singing a bafflingly long song about loneliness and realizing that they’re kindred spirits. This burgeoning young love is put on hold when Tenar is kidnapped by the earstwhile slavers, who, as it happens, are collecting sacrifices for a wizard named Cob, who is courting immortality and thus killing all magic in the land. Arren, terrified of death, is seduced into joining him, and since Sparrowhawk is a Very Busy Man, it is left to Therru to rescue Arren and Tenar. Afterwards, briefly, inexplicably, and unprompted, she turns into a dragon.

Fans of Le Guin’s book series will recognize many elements and plot points reshuffled into new formations in this description—The Farthest Shore is probably its driving inspiration, but Arren’s “possession” is a clear callback to Sparrowhawk’s in A Wizard of Earthsea, and Therru is only introduced in Tehanu. The movie’s resemblance to the Journey of Shuna graphic novel is also somewhat sideways, in that many Ghibli films, Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä most prominently, borrowed from it. But lines of similarity are some of the least interesting ways to read an adaptation—especially with a film so lifeless and weird. Did I mention that Therru randomly turns into a dragon?

Most important to me, though, are the ways that this movie fails the mission of the creators’ larger bodies of work. I wrote recently about Le Guin’s delicate dance between allegory/myth and emotional realism. It’s a dance that her works almost always step gracefully, that make for a poetry and richness that invites readers to return and reread over and over again. Studio Ghibli has much the same effect; though they are often compared to Disney, Ghibli deals in Big Ideas and unreal scenarios through very real, flawed humans. Tales of Earthsea keeps the big ideas and fantastical elements of those sources, but erases the human emotion. I found myself at turns confused by characters’ motivations (why did Arren kill his father?) and annoyed by the convenient ways that they slotted into the film’s themes (Therru decides she likes Arren just in time to rescue him). It’s difficult to appreciate a story’s take on ideas about mortality and love when those ideas are delivered by caricatures.

Another aspect of both the Earthsea series and Ghibli that I find laudable is their willingness to take their young audiences seriously. It’s another feature that differentiates Ghibli from Disney, and another that invites Le Guin readers of all ages into the pages of Earthsea. Both creators make fiction for children that allow them to explore real emotion and sometimes real trauma, safely. Tales of Earthsea, though, explains its own plot at every turn, having its characters narrate the film’s themes to one another. It portrays bloodlust, slavery, death, and prejudice without ever really exploring their consequences. It’s not that the film talks down to its young audience members; it’s that it doesn’t seem to know who its audience is at all.

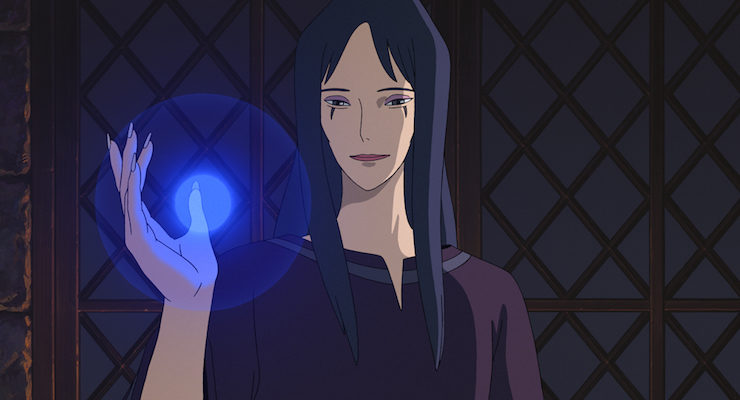

And finally, the politics. The film’s whitewashing has been much-discussed—and rightfully so—by Le Guin herself and many others, and so I want to touch on another egregious piece of erasure: gender. Ghibli and Le Guin alike are known for their excellent, albeit very different, explorations on gender—willful, independent young girls in the case of the former, and boundary-testing folk of all genders in the latter. Tales of Earthsea keeps the iconic Ghibli protagonist in spunky Therru, but stumbles again and again to create any kind of meaning out of her spunk, instead relegating her to teaching Arren how to be Good. Tenar, my favorite character in the novels, is reduced from a morally complicated cult survivor to doting mother and patient lover and acolyte. Most offensive, though, is the movie’s villain, Cob.

An obsession with immortality is interpreted here as vanity, and as we all know, vanity is the domain of women—therefore the horror of Cob is illustrated through the unforgivable act of gender deviance. Feminine features, a whispering androgynous voice, and most horrible of all, the seduction of a young boy, make him a queer trope to be reckoned with, and a counterpoint to these creators’ otherwise fascinating record of gender critiques.

Buy the Book

The Books of Earthsea

Between this and the equally notorious 2004 Sci-Fi adaptation of Earthsea, it’s easy to see why some might consider the series unadaptable. Perhaps out of some misplaced optimism, I disagree. Certainly the quietness of Le Guin’s story-telling and the vastness of her world and mythos might lend themselves better to forms other than film—graphic novels, perhaps, or audio, or even an RPG—but we might also just not have found the right team of creators yet. As Gorō Miyazaki tried his hand at Earthsea, even, Hayao simultaneously crafted his own adaptation of another beloved fantasy novel, Diana Wynne Jones’ Howl’s Moving Castle, arguably one of the best in Studio Ghibli’s oeuvre. I’d not only try on another Earthsea adaptation, I’d try another Ghibli one. This film was a disappointment, but the pairing did make sense. It was, more than anything, a wasted opportunity.

And if anyone wants to make me eat my words in the next few years, that’s fine too.

Em Nordling reads, writes, and manages research in Louisville, KY.